2017 ended as the deadliest and most destructive fire season in California’s history with over 9,000 fires burning nearly 1.3 million acres and taking the lives of 46 people. The repercussions of these fires are extensive, impacting lives and livelihoods, carbon emissions, air quality, water supply, wildlife, natural ecosystems, and more.

There is such a thing as too many trees

After interrupting the natural fire cycle through decades of fire suppression, California forests now hold an average of more than 300 trees per acre – that’s six times the historical level from a century ago. This excess vegetation is neither natural nor beneficial but rather artificially increases the risk and severity of wildfire. Combined with the effects of climate change, it is no surprise that 40 percent of the U.S. Forest Service’s 193 million acres of public forest and grasslands are at “high or very high risk of catastrophic wildfires”.

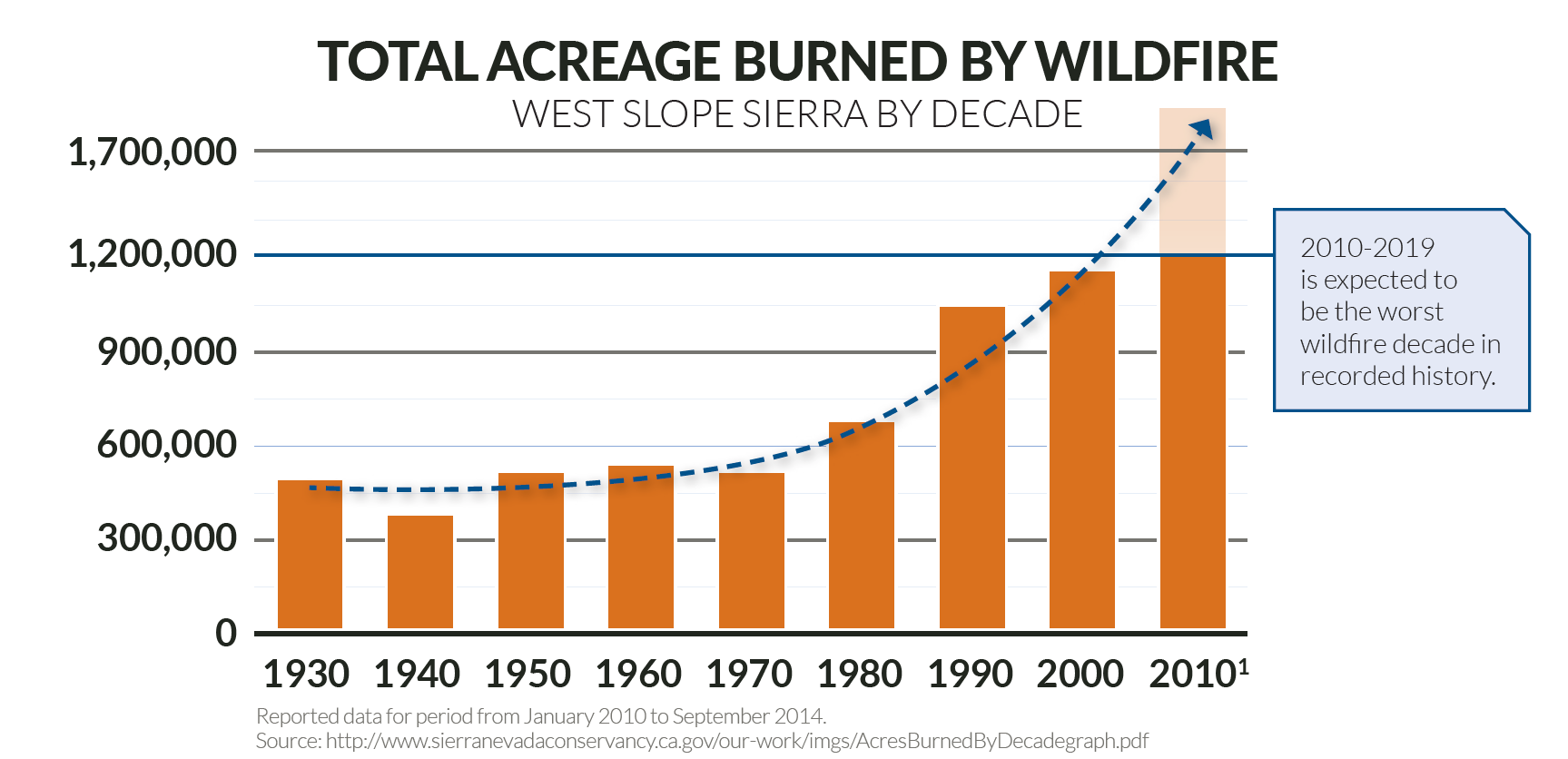

Recent trends indicate that severe wildfire is here to stay, and will likely only get worse absent a significant change in the status quo. As a result of both overgrown forests and climate change, wildfire seasons have gotten longer by 78 days over the last 50 years. In addition, individual wildfires themselves are larger and more severe. In California’s Sierra Nevada, the current amount of burnt acreage is . Scientists have observed that wildfires across the West, in particular, are burning larger and for a progressively longer portion of the year with seemingly no end in sight.

Forest restoration—the strategic removal of brush and shrubs and selective thinning of trees—could help return forests to a healthier state. However, the Forest Service and other land managers are far short of the resources they need to do to the job at the scale required.

The benefits (and beneficiaries) of forest restoration

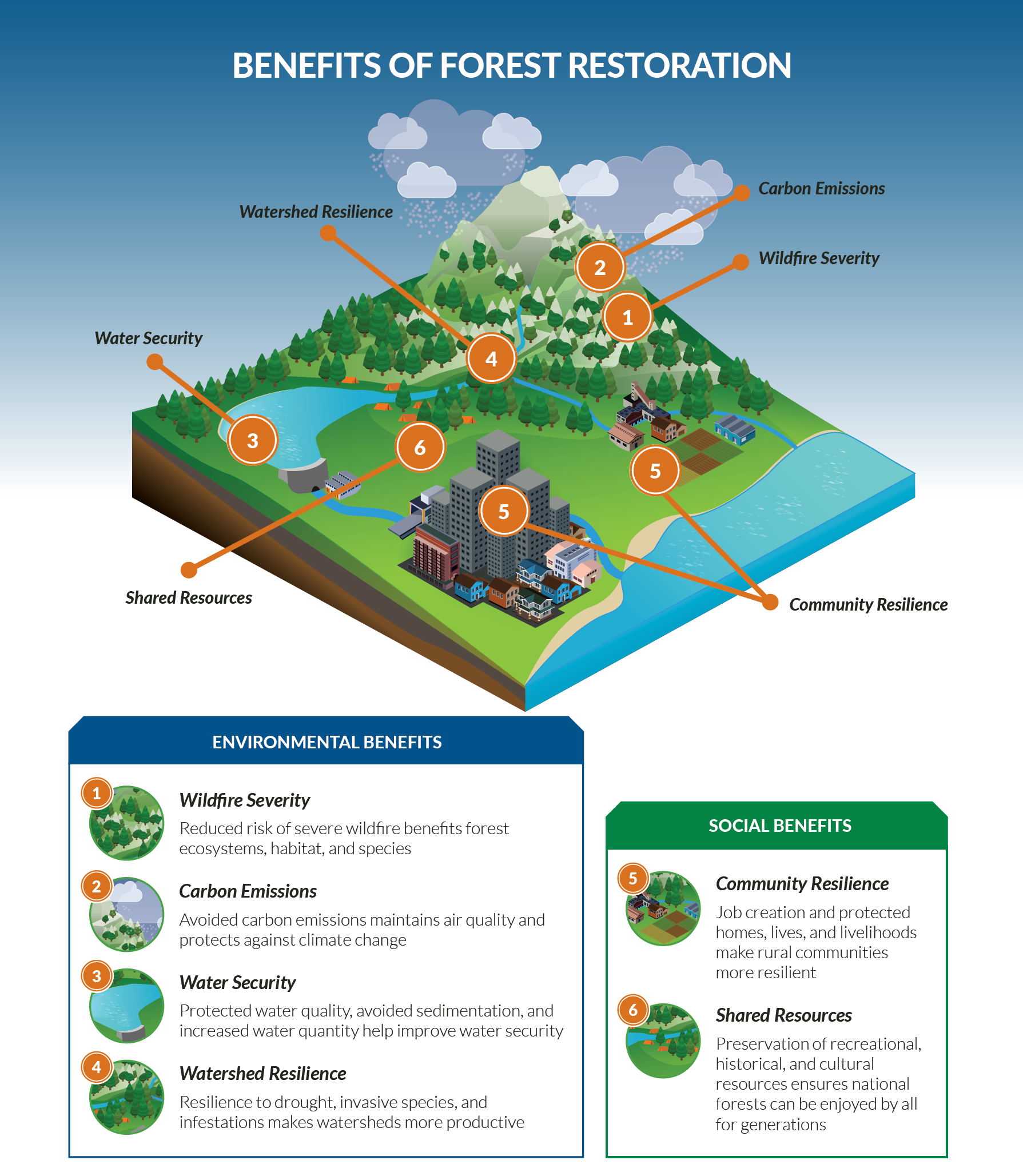

While it may seem counterintuitive, removing (small diameter) trees through restoration creates a healthier and more resilient ecosystem by returning overgrown forests to their natural state. In fact, the benefits of forest restoration are numerous and widespread – forests restored to a more natural density face a lower risk of severe wildfire, which protects water supply and watershed resilience while avoiding devastating carbon emissions from wildfires. These impacts are particularly crucial in California, where more than 60% of the state’s developed water supply originates as snowpack in the Sierra Nevada.

In the fight against climate change, forests can be an asset or a liability. A well-functioning forest acts as a much-needed carbon sink. In fact, US forests offset 10% – 20% of domestic emissions from burning fossil fuels each and every year. Snowpack accumulating in forests, as well as forest products, such as timber, enable renewable energy generation in the form of hydroelectricity and biomass power, respectively. When hydro and biomass resources achieve higher utilization, the electricity they generate offsets the demand for carbon-emitting sources of power, such as natural gas and coal. However, a forest will only be able to sequester carbon, retain snowpack, and provide timber if it does not burn down.

Instead, when a catastrophic wildfire spreads, the trees, soil, and ecosystems are destroyed. With a lack of trees to provide shade and burnt soil contaminating snowpack, water resources and hydro generation are both at risk. The air that we breathe, the water that we drink, and the communities in which we live all rely on healthy forests in one way or another.

Given the diverse impacts and economic value that restoration creates, a wide array of beneficiaries in addition to the Forest Service is impacted. Water and hydroelectric utilities can benefit from protected infrastructure and water quality, avoided sedimentation, and even augmented water quantity for hydropower and consumption. In California, where 1 in 3 homes is at risk of wildfire, the state government benefits from community resilience, rural job creation, and avoided carbon emissions associated with large fires. Even transportation companies, ski resorts, and breweries can be powerful beneficiaries of restoration.

Despite the financial, social, and environmental benefits that restoration would create, the Forest Service lacks the resources to implement treatments on public and private land across the Western U.S. That’s due to a vicious cycle known as “fire borrowing,” in which the Forest Service pays to fight today’s fires out of the funds designed to prevent tomorrow’s.

In fact, the Forest Service now spends more than half of its budget just to put out fires. Left unchecked, fire suppression is expected to rise to two-thirds of the total budget by 2021, resulting in nearly $700 million less available each year for proactive restoration and other initiatives to promote forest health.

The Forest Resilience Bond

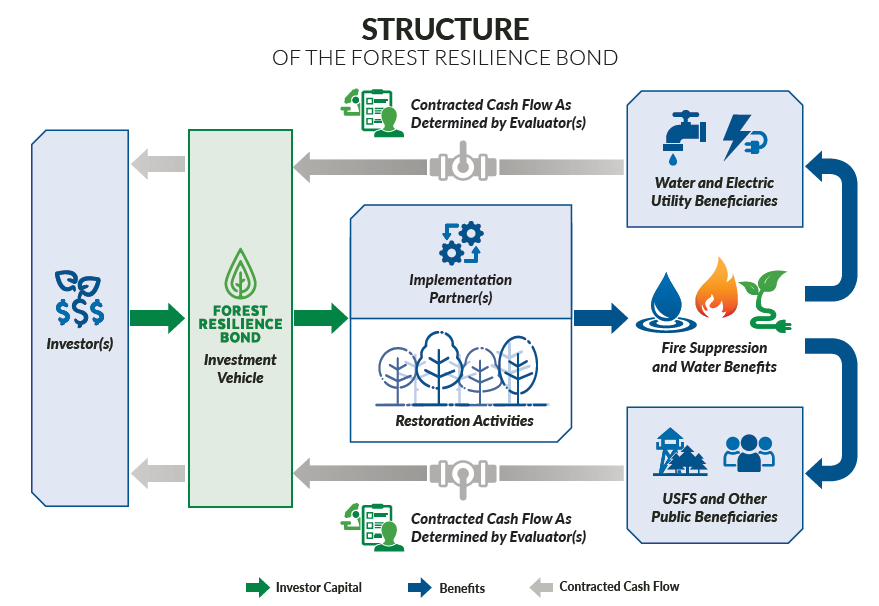

In many cases, the value of forest restoration to its many beneficiaries far exceeds the costs and would make a compelling economic case for investment—if only such opportunities existed. Recognizing this potential, Blue Forest Conservation is developing a new approach called the Forest Resilience Bond (FRB). In collaboration with the World Resources Institute and Encourage Capital, the FRB is a first-of-its-kind tool that brings together the beneficiaries of forest restoration with an unlikely ally: private investors.

In its most basic form, the FRB is a collaborative investment in forest health. It is a public-private partnership that enables private capital to finance much-needed forest restoration. Beneficiaries of the restoration work make cost-share and pay-for-performance payments over time (up to 10 years) to provide investors competitive returns based on the project’s success.

For example, once investor capital is used to implement the restoration treatments, investors earn back their money from payments by beneficiaries such as the following:

- The Forest Service, paying for decreased risk of severe fire;

- Electric utilities, paying for increased hydroelectricity generation, avoided sedimentation, and protected infrastructure;

- Water utilities, paying for protected water quality and improved water volumes; and

- State governments, paying for avoided fire suppression costs, avoided carbon emissions, protected communities, and job creation.

Blue Forest Conservation seeks to scale forest restoration across forests in need, not through increases in public or philanthropic funding, but by harnessing private capital to complement existing funding and facilitate investment in the management of public lands.

Private capital as an untapped resource for conservation

Private capital is no silver bullet – it requires thoughtful governance and incentives to ensure that natural resources and public agencies are protected, and it may not be an appropriate funding source for every environmental challenge. But with billions of dollars earmarked for conservation that remain undeployed due to a lack of investment opportunities, willing private investors have too often been sidelined. The FRB helps fill this void by bringing together investors, government agencies, utilities, private companies, and state governments to sustainably fund restoration today in order to avoid catastrophe and costs tomorrow.

The time to act is now. Wildfire seasons are getting longer and more severe, tree mortality has reached unprecedented levels, and climate change suggests that drought will be more persistent while temperatures continue to rise. These trends will be catastrophic for forests and for society as a whole. Private capital can play a role in building a more sustainable future. We just have to give investors the tools to do so.

|

Leigh Madeira is a Co-Founder and Partner at Blue Forest Conservation, a Public Benefit Company leveraging financial innovation to create sustainable solutions to environmental challenges. Prior to founding Blue Forest, Leigh researched energy investment opportunities in the equity and fixed income markets at Hotchkis and Wiley Capital Management, worked as an analyst at the shareholder activism firm Relational Investors, and was an investment banking analyst for Credit Suisse. Leigh’s experience with investments both large and small – from multi-billion dollar deals to $300 microloans while serving as a Kiva Fellow in Ecuador – makes her uniquely positioned to understand the financial needs of a diverse set of stakeholders. Leigh earned an MBA with honors from UC Berkeley Haas School of Business, holds a BBA in Finance from the University of Notre Dame, and is a CFA charterholder. |