Though separated by an ocean and a language, we share a desire to do what is best for our citizens and our planet. That means putting aside parochial politics and embracing the global challenge of fighting climate change. In doing so, we can create a cleaner, healthier, more prosperous world for Parisians, Pittsburghers and everyone else on the planet.

– Mayors Ann Hidalgo (Paris) and William Peduto (Pittsburgh)

This summer, President Trump pulled the United States out of the Paris Climate Agreement, claiming to be more concerned about Pittsburgh and other American cities than what the world was trying to do in Paris to fight climate change. Mayors and other local leaders around the country had an entirely different notion of how best to represent their constituents when it comes to climate change.

With the United Nations’ climate-change conference in Bonn recently wrapped up – after a year full of extreme and unprecedented weather events – it’s a good time to reflect on the state of climate leadership and the role of local governments as 2017 comes to a close.

This year, the U.N. Climate Change conference (Conference of Parties 23) was focused on establishing the first draft of “the Paris Rulebook” to guide the implementation of the Paris Climate Accord that governs how nations monitor carbon emissions and reports on their contribution toward their specific targets.

Collectively, the Paris Agreement aims to respond to the climate-change threat by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

With Syria and Nicaragua recently signing on to the Paris Accord, the United States is now the only country on the planet that has declined to be a part of the agreement.

Despite the federal administration’s retreat from the climate-change community, the United States was nevertheless well represented in Bonn by local and state leaders and private-sector champions.

A new initiative launched this summer, America’s Pledge, co-chaired by Governor Jerry Brown and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, released the Phase One report, outlining current climate actions and potential areas of action for coalition members, which include more than 2,300 states, tribal nations, counties, cities, businesses, nonprofits, universities and colleges.

This initiative adds to a growing list of subnational leaders, including the Under2 Coalition for states, cities and regions, the Global Covenant of Mayors, the private sector’s We Mean Business, the U.S. Climate Mayors, the U.S. Climate Alliance and We Are Still In – which now has 2,500 signatures representing more than 130 million Americans and $6.2 trillion of the U.S. economy.

If all the U.S. actors participating are taken as a whole, they represent a combined GDP larger than all but two of 197 Parties to the Framework Convention.

Priority Actions at the Local Level

Cities, especially in the U.S., will be critical to continuing progress on climate change: 20% of the actions needed to fight climate change must be accomplished by cities, according to a new McKinsey report, “Focused Acceleration.”

The report analyzed 450 emissions reduction actions and prioritized 12 opportunities across four action areas that have the greatest potential in most cities to curb emissions and put them on a 1.5°C pathway through 2030. Focusing on four high-impact areas will result in the highest impact, the report says:

1. Decarbonize the electricity grid.

Cities can play an essential role by setting clear decarbonization goals, aggregating demand for and investing in renewables, promoting energy efficiency, and shifting more urban energy consumption to electricity (especially in transportation and heating). By accelerating those efforts, according to McKinsey, cities could achieve “35 to 45% of the total emissions reductions needed [by 2030] at a cost as low as $40 to $80 per megawatt-hour.”

From Pittsburgh to San Diego, communities across the nation are setting goals to achieve 100% renewable energy from solar, wind and other renewable sources by 2035.

Many jurisdictions are forming Community Choice Aggregation entities (CCAs) as a core strategy to increase renewable energy and local authority to manage energy resources portfolios and investments. To date, CCAs are forming in more than 80 jurisdictions across California.

Local governments can also make it easier to site and expedite permitting for solar energy facilities. In California, the City of Richmond turned a former brownfield into49-acre solar farm, spearheaded by Marin Clean Energy, a Community Choice Aggregator, that will create 100 new jobs and generate enough energy to power more than 3,000 homes. A 34-acre site is under development in Bakersfield, just one of three solar sites planned in Kern County that is expected to generate enough to power more than 6,000 homes.

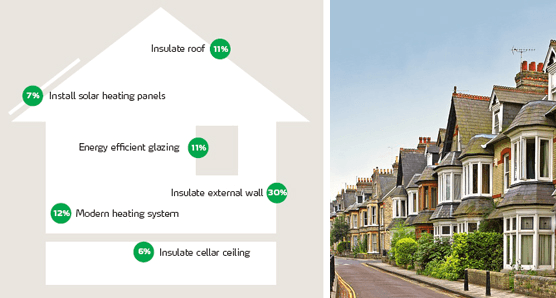

2. Make buildings work better.

Heating and cooling the world’s buildings produces around 40% of global energy emissions. The McKinsey report urges cities to take such actions as “raising building standards for new construction, retrofitting building envelopes, upgrading HVAC and water heating technology, and implementing lighting, appliance, and automation improvements.”

Buildings are long-lasting infrastructure, averaging between 30 and 50 years, so getting them right (or wrong) reverberates far in the future. Accelerating action in this area, McKinsey says, “can close 20 to 55% of the gap between current emissions trends and 2030 abatement targets, depending on the local climate and population growth of the city, at an average cost of $20 to $100 per metric ton of CO2 equivalent.”

California’s Title 24 building standards have increasingly improved the energy and water efficiencies of new buildings. Some cities – such as Brisbane, Fremont, Healdsburg, Lancaster, Marin, Mill Valley, Novato, Palo Alto, Portola Valley, San Francisco, San Mateo and Santa Monica – have passed “reach codes” that require even more stringent energy standards for newly constructed buildings, additions, alterations, and repairs to existing building. For more info

Local governments across the state are also adopting Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) programs that help homeowners and businesses save energy or water by providing financing to install solar, more efficient windows, furnaces or water heaters. The financing is paid back through the energy savings, so there is no upfront cost. PACE is currently available to more than 88% of California homes.

3. Change how people get around.

Because transportation is responsible for almost 40% of greenhouse gas emissions in California, reducing and cleaning car travel will be critical to meeting our climate goals and improving community health. The Ahwahnee Principles for Smart Growth outline how communities can improve urban design to create complete communities where people can meet their daily needs through a range of transportation options including walking, biking and public transit.

Regional sustainable community strategies – now required under Senate Bill 375 – have helped to focus growth on infill and transit-oriented development.

Another key element to California’s goal of getting emissions 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 is reducing petroleum use in vehicles by 50%. California also has a goal to have 1.5 million zero-emission cars on the road by 2025.

Local governments are also setting ambitious goals to eliminate internal combustion engines and increase electric vehicles. A dozen cities have signed a Fossil-Fuel-Free Streets Declaration – Los Angeles and Seattle in the U.S., joined by London, Paris, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Quito, Vancouver, Mexico City, Milan, Auckland and Cape Town -which includes a promise to procure only zero-emission buses from 2025 and ensure a major area of their cities are zero-emission by 2030.

Accelerating efforts in these areas, the McKinsey report calculates, “can contribute emissions reductions equal to 20 to 45% of 2030 targets, depending on urban income levels and population density.” These kinds of efforts will also increase the livability and attractiveness of cities while reducing local air pollution.

4. Use less and waste less.

Cities have a variety of ways to use less and waste less: “first reducing waste upstream; then repurposing as much useful finished product as possible; then recycling, composting, and otherwise recovering materials for use; and finally, managing disposal to minimize emissions of any remaining organic matter.”

Organic matter emits methane as it decomposes, which is a much more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide in the short-term, so it’s key to minimize organic waste, and take steps to capture and use the methane emissions from landfills.

The ultimate goal is a “circular economy,” in which there is no waste: all materials would be recaptured and reused. Depending on its starting point, McKinsey estimates, a city can get about 10% of its needed emission reductions from waste-management strategies.

Food to Share, a program started in 2015 by the Fresno Metro Ministry, is a great example of win-win solutions that can benefit community members and the environment- simultaneously addressing hunger, reducing waste, and generating energy. They collect excess food from schools, farmer’s markets, food service facilities, restaurants, supermarkets, food distributors, hospitals, institutional cafeterias, growers and packers and gleanings. They then distribute the food to churches, food kitchens, pantries and distribution centers who get the food to the community in need.

Food that is unable to be used for healthy consumption goes to an anaerobic digester, which is better for the environment and air quality and creates a low-carbon renewable source of energy. Over a period of just four months, Food to Share distributed nearly 180,000 pounds of donated and recovered food to neighborhoods in need, reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 396,000 pounds.

Climate Action Crosses Borders

Climate impacts cross political lines and geographic barriers. The scale of these factors intensified the impacts of the natural disasters we’ve faced in 2017 and clearly call for a new level of leadership and sense of urgency. While our federal government steps back from climate leadership, local and state leaders must step forward into the breach with even more passion, policy and persistence.

|

Kate Meis is the Executive Director of the Local Government Commission (LGC)— a nationally recognized nonprofit connecting local leaders, implementing innovative solutions and advancing smart-growth policies. Founded in 1980, LGC has over 700 members, 40 staff and 70 CivicSpark Fellows working on smart growth initiatives throughout the state and the Nation. Kate is a Senior Fellow of the American Leadership Forum and has been recognized for her climate-change work by the Chronicle of Philanthropy as one of the nation’s “40 under 40 Young Leaders Who Are Solving the Problems of Today – and Tomorrow”. Prior to joining Local Government Commission in 2006, Meis conducted research for the UC Davis Department of Environmental Science and Policy, Transportation Alternatives of Marin, 4-H Center for Youth Development, and the University of California Cooperative Extension. She earned a M.S. degree in community and regional development from UC Davis, and received a bachelor’s degree in sociology from CSU-Sonoma.

|